Home » Digital Health

Category Archives: Digital Health

Peterson Center Kills the Diabetes Industry Dead

Last week the Peterson Health Technology Institute (PHTI, part of the Peterson Center on Healthcare) published the seminal report on the diabetes digital health industry, concluding that (with the clear exception of Virta, which we have also strongly endorsed) the minor health improvements claimed by Livongo, Omada and others nowhere near offset the substantial cost of these programs. To which we reply:

We, on the other hand, have known this since 2019. PHTI’s excuse, such as it is, is that it was formed in 2023. We’ll let it go this time…

The Likely Impact of the Findings

The report shows that digital health vendors (once again, with the exception of Virta, which emerged as the clear – and only – winner from this smackdown) are “not worth the cost.” We would strongly recommend reading it, or at least the summary in STATNews. It is quite comprehensive and the conclusion is well-supported by the evidence.

In the short run, the effect of this report should be Mercer renouncing its “strategic alliance” with Livongo (“revolutionizing the way we treat diabetes”) and returning the consulting fees it earned for recommending them to their paying clients. (Haha, good one, Al.)

This was a rookie mistake by Mercer in the first place. Not forming the “alliance,” but rather announcing it. The whole point of benefits consultants making side deals with vendors is to do it on the QT so clients don’t notice. Hence, I’m not saying Mercer should actually renounce Livongo and harm their business model. Just that they should pretend to.

In the long run, this report should signal the end of the digital diabetes industry, meaning Livongo, Omada, Vida and a couple I’ve never even heard of. The bottom line: private-sector employers using digital solutions for diabetes may be violating ERISA’s requirement that health programs benefit employees by being “properly administered.”

The Empire Better Not Fight Back

Inevitably, the well-funded diabetes industry will fight back against PHTI’s report and “challenge the data.” They’d be right in one respect: the data does need to be “challenged.” However, it’s for the opposite reason: PHTI went far too easy on these perps.

Here is what I would have added to the report, had they retained my services. (And I’d be less than honest if I didn’t admit I had hinted they should, but I think by then their budget was fully committed.) These points will inevitably come to light in the event of a “challenge.”

Second, matched controls are invalid because you can’t match state of mind. Ron Goetzel, the integrity-challenged leader of what Tom Emerick used to call the “Wellness Ignorati,” demonstrated that brilliantly, naturally by mistake. Take a looksee at what happens when you match would-be participants to non-participants – but without giving the former a program to participate in. The Incidental Economist piled on. And then the Wellness Ignorati tried to erase history, recognizing they had accidentally invalidated their entire business model. Diabetes is no different. There’s a reason the FDA doesn’t count studies that compare participants to non-participants, it turns out. PHTI accepted them as a control.

Third, along with sample bias there is investigator bias. Livongo’s main study was done by — get ready — Livongo. Along with some friends-and-relations from Eli Lilly and their consultants. PHTI assumed investigators were on the level. I’d direct them to Katherine Baicker’s two studies on the wellness industry. The first – whose “3.27-to-1 ROI” pretty much greenlit the wellness industry – was a meta-analysis of studies that were done – get ready – by the wellness industry. It has been cited 1545 times. The second, featuring Prof. Baicker’s own independently funded primary research, found exactly the opposite. It has been cited 16 times.

Don’t get us started on Livongo

Oops, make that a million and one.

Drawing undue attention to unwanted publicity has henceforth been termed The Streisand Effect. Right now this PHTI report is mostly of interest to the cognoscenti. Most of its customers won’t notice.

Why? Because what we say about wellness is likely also true here: “There are two kinds of people in the world. People who think diabetes digital health works, and people who have a connection to the internet.”

Vivify Springs Back to Life

In politics today, one strategy dictates: never apologize, never admit error, never correct an earlier misstatement. If that strategy works, the CEO of Vivify would carry all 50 states, not to mention the District of Columbia. Vivify just updated their website, without correcting any of the numbers that I pointed out in 2015 simply didn’t add up. Maybe they didn’t know their arithmetic was wrong, even though presumably sometime in the last three years at least one of their employees earned their GED.

Not only did they keep the original “math” on the new website, they also kept the original grammar and spelling. Consequently, just like they updated their website by keeping the original intact, I am “updating” my own posting below simply by keeping the original intact.

With one addition: in 2015 I failed to congratulate them for reducing the total annual cost of care for people with heart failure to $1231. To put this feat in perspective, that’s about 80% less than the average annual cost of care for people whose hearts haven’t failed.

The population health industry never ceases to delight us with its creativity. Vendors come up with ways of demonstrating their incompetence that are so creative we are compelled to use screenshots to back up our observations. Otherwise no one would believe us.

Consider Vivify. They reported on a study of in-home post-discharge telemonitoring led by a:

Not being able to spell the name of his own occupation is the good news. The bad news is, the “principle investigator” also can’t write, can’t count, and – most importantly for someone who claims to be a “principle investigator” — can’t investigate. (Those shortcomings aside, this is a very impressive study. For instance, the font is among the most legible we’ve ever seen.)

The Writing

There is some redundancy in the writing, but, giving Vivify the benefit of the doubt, perhaps the extra verbiage reflects the principle investigator’s concern that someone might miss the nuances or subtleties in his exposition. Examples:

- Vivify’s home monitoring system is “simple and easy”;

- The patient receives a “weight scale”;

- They had an “ROI of $2.44 return for every dollar invested”, and…

- “With appropriate connectivity, patients could engage in real-time interactive videoconferencing.”

Needless to say, these product attributes are very intriguing, so intriguing that you may want to learn more about the company. They are only too happy to oblige, making sure we catch yet another nuance:

The Arithmetic

The study claims the average patient’s cost declined $11,706, for a 2.44-to-1 ROI. Doing the math, that means Vivify’s post-discharge in-home self-care telemonitoring costs roughly…let me just get out my calculator here…$4797/patient. At that price, why rely on self-monitoring? Why not just move a nurse in?

The Principle Investigation

In general, Vivify targets patients with “specific chronic illnesses,” including pneumonia. (Vivify, I don’t know how to break this to you gently, but: pneumonia isn’t a chronic illness, specific or otherwise. No one ever says: “I was diagnosed with pneumonia a few years ago, but my doctor says we’re staying on top of it.”)

However, for this investigation, only CHF was targeted: specifically, a cohort of 44 recently discharged CHF patients with an average age of 66. This raises the question: How did the principle investigator scrounge up a cohort of 44 discharged CHF patients with an average age of only 66? More than half of CHF discharges are over 75. It’s statistically impossible to randomly select 44 CHF discharges with an average age of 66. And – isn’t this a lucky coincidence – the study claimed a large (65%!) reduction in readmission rates but readmission rates are already much lower for younger patients. Once again, not a word of explanation.

Because Vivify’s misunderstanding of basic arithmetic and study design boggled even our minds (and our minds are not easily boggled, because we mostly blog about wellness), we decided to give them a chance to explain directly that we might have missed something. Further, because these explanations would have taken them 15 minutes if indeed we were missing something obvious, we offered them $1000 to answer them, money they decided to leave on the table. (Anyone have questions for me? Send me $1000 and I will happily spend 15 minutes answering them.)

This email to Vivify is available upon request. [Or at least it was in 2015. I’d have to hunt for it now.]

We don’t even know what the 65% reduction is compared to. Usually – and call us sticklers for details here – when someone claims a 65% reduction in something vs. something else, they offer some clues as to what the “something else” is. Are they saying 35% were readmitted? Or 66-year-olds are readmitted 65% less than 75-year-olds? Or that they scrounged up yet another group of 66-year-olds with a CHF hospitalization and compared the two groups but forgot to mention this other group?

Savings Claims

My freshman roommate was like the bad seed in the old Richie Rich comics. Among other things, he would have a snifter of cognac before bed, whereas I had never tasted cognac and thought a “snifter” was for storing tobacco. We didn’t get along and at one point I accused him of being decadent.

“Decadent, Al? Let me tell you about decadent. I spent last summer at a summer camp – everyone was there, Caroline Kennedy, everyone – where we played tennis on the Riviera for a month and then went skiing in the Alps.” I had to admit that was indeed decadent.

“Al,” he replied. “I haven’t even gotten to the decadent part yet.”

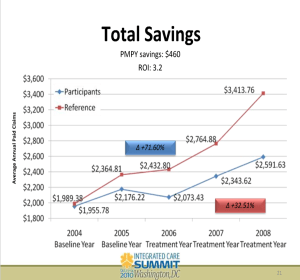

Likewise, we haven’t even gotten to the clueless part yet: the savings claim. Remember that $11,706 savings claim above? Well, read that passage again–it turns out that represents a “90% decrease in the cost of care.” Apparently, the patients cost $12,937 when they were in the hospital, but after they went home, they only cost $1231. (We have no idea how that squares with the other finding, that the Vivify system itself costs $4797, based on the “ROI of $2.44 return for every dollar invested.”.)

The irony is that other vendors in this space really do save money and really do measure validly. It’s one thing to make up outcomes in wellness. That’s a core part of the industry value proposition. But, unlike wellness vendors, tele-monitoring vendors other than Vivify typically know the basics: what they are doing, how to measure outcomes, how to save money–and how to spell “principal investigator.”

Vivify Brings Incompetence to Life

The population health industry never ceases to delight us with its creativity. Vendors come up with ways of demonstrating their incompetence that are so creative we are compelled to use screenshots to back up our observations. Otherwise no one would believe us.

Consider Vivify. They reported on a study of in-home post-discharge telemonitoring led by a:

Not being able to spell the name of his own occupation is the good news. The bad news is, the “principle investigator” also can’t write, can’t do simple arithmetic, and – most importantly for someone who claims to be a “principle investigator” — can’t investigate. (Those shortcomings aside, this is a very impressive study. For instance, the font is among the most legible we’ve ever seen.)

The Writing

There is some redundancy in the writing, but, giving Vivify the benefit of the doubt, perhaps the extra verbiage reflects the principle investigator’s concern that someone might miss the nuances or subtleties in his exposition. Examples:

- Vivify’s home monitoring system is “simple and easy”;

- The patient receives a “weight scale”;

- They had an “ROI of $2.44 return for every dollar invested”, and…

- “With appropriate connectivity, patients could engage in real-time interactive videoconferencing.”

Needless to say, these product attributes are very intriguing, so intriguing that you may want to learn more about the company. They are only too happy to oblige, making sure we catch yet another nuance:

The Arithmetic

The study claims the average patient’s cost declined $11,706, for a 2.44-to-1 ROI. Doing the math, that means Vivify’s post-discharge in-home self-care tele-monitoring costs…let me just get my calculator out here…$4797/patient? At that price, why rely on self-monitoring? Why not just move a nurse in?

(Note for the literal-minded: the ROI language is slightly different here than the passage we quoted, which appears elsewhere in the case study.)

The Principle Investigation

In general, Vivify targets patients with “specific chronic illnesses,” including pneumonia. (Vivify, I don’t know how to break this to you gently, but: pneumonia isn’t a chronic illness, specific or otherwise. No one ever says: “I was diagnosed with chronic pneumonia a few years ago, but my doctor says we’re staying on top of it.”)

However, for this investigation, only CHF was targeted: a cohort of 44 recently discharged CHF patients with an average age of 66. This raises the question: How did the principle investigator scrounge up a cohort of 44 discharged CHF patients with an average age of only 66? More than half of CHF discharges are over 75. It’s statistically impossible to randomly select 44 CHF discharges with an average age of 66. And – isn’t this a lucky coincidence – the study claimed a large (65%!) reduction in readmission rates but readmission rates are already much lower for younger patients. Once again, not a word of explanation.

Because Vivify’s apparent level of misunderstanding of basic arithmetic and study design boggled even our minds (which is difficult to do, given that we mostly blog about wellness), we decided to give them a chance to explain directly that we might have missed something. Further, because these explanations would have taken them 15 minutes if indeed we were missing something obvious, we offered them $1000 to answer them, money they decided to leave on the table. (Anyone have questions for me? Send me $1000 and I will happily spend 15 minutes answering them.)

This email to Vivify is available upon request.

We don’t even know what the 65% reduction is compared to. Usually – and call us sticklers for details here – when someone claims a 65% reduction in something vs. something else, they tell us what the “something else” is. Are they saying 35% were readmitted? Or 66-year-olds are readmitted 65% less than 75-year-olds?

Savings Claims

My freshman roommate was like the bad seed in the old Richie Rich comics. Among other things, he would have a snifter of cognac before bed, whereas I had never tasted cognac and thought a “snifter” was for storing tobacco. We didn’t get along and at one point I accused him of being decadent.

“Decadent, Al? Let me tell you about decadent. I spent last summer at a summer camp – everyone was there, Caroline Kennedy, everyone – where we played tennis on the Riviera for a month and then went skiing in the Alps.” I had to admit that was indeed decadent.

“Al,” he replied. “I haven’t even gotten to the decadent part yet.”

Likewise, we haven’t even gotten to the best example of arithmetic-gone-wild: the savings claim. Remember that $11,706 savings claim above? Well, read that passage again–it turns out that represents a “90% decrease in the cost of care.” Apparently, the patients cost $12,937 when they were in the hospital, but after they went home, they only cost $1231. (We have no idea how that squares with the other finding, that the Vivify system itself costs $4797, based on the ROI of 2.44, or, as they put it, “an ROI of $2.44 return for every dollar invested.”.)

The irony is that other vendors in this space really do save money and really do measure validly. It’s one thing to make up outcomes in wellness. That’s a core part of the industry value proposition. But, unlike wellness vendors, tele-monitoring vendors other than Vivify typically know the basics: what they are doing, how to measure outcomes, how to save money–and how to spell.